Tag archives for: Norman Foster

Successful architecture careers don’t happen by accident. Just like well-designed buildings, they’re the result of careful planning.

While there are countless metrics you can consider when going about this planning, one of the most important is the city within which you’ll work.

That’s why we’ve put together a list of the three best cities in the country for professionals who are serious about pursuing successful architecture careers.

We based this list on the all-important factor of salary but also on other unique traits worth considering.

1. Atlanta, Georgia

Georgia is one of the best states for architects, so it should come as no surprise that many point to its capital as the best city for this profession.

Even though Atlanta is home to countless high-paying careers, architects are among the top 50 best-paid. Architectural managers even crack the top 20, alongside lawyers, several doctors, and even physicists.

Of course, Atlanta also has an impressive history of hosting incredible buildings from a number of different styles, so you won’t be lacking for inspiration. That said, you won’t be lacking for competition, either. Atlanta is home to a few award-winning architects, though that also means plenty of impressive firms looking for new talent.

2. West Palm Beach, Florida

Located about an hour-and-a-half north of Miami, West Palm Beach has plenty going for it aside from the incredible weather. On average, the highest-paid architects in the country call West Palm Beach home. That average salary is an impressive $120,380 a year. Florida does not have a State income tax either.

The city is also full of architecture firms – well over three dozen of them – so you shouldn’t have too much trouble beginning your job search.

Many world-class architects choose West Palm Beach for their headquarters because there is no lack of developers with large budgets who appreciate beautiful designs.

The city also attracts talent from across the world for the same reason. As just one example, look no further than the $100-million expansion of the Norton Museum, which was designed by Norman Foster, a winner of the Pritzker Architecture Prize.

3. Chicago, Illinois

For our third spot on the list, we head north to the Windy City. Chicago’s history as a city of architectural wonders probably began in 1893 during the World’s Fair. It debuted the first ever Ferris Wheel but also brought in some of the time’s most prominent architects to contribute their talents.

Though only one major structure survived, Chicago’s tradition of welcoming incredible architects has carried on. Over the years, famous architects like William Le Baron Jenney and Frank Lloyd Wright have all left their mark on Chicago.

Modern architects looking to do the same won’t be disappointed. While the pay isn’t as much here, the cost of living is also much lower, meaning your salary will stretch a lot further.

Work with Experts Who Specialize in Launching Architecture Careers

Want more help getting your career off the ground?

At Consulting For Architects, we specialize in both project placement and permanent placement for professionals who are dedicated to pursuing successful architecture careers. If you’d like the help of an experienced team of experts, please feel free to contact us today.

Now that summer is in full swing, all thoughts of cramming to finish overdue projects have likely drifted away. But just because you’ll be reading trashy magazines at the beach for the next month, doesn’t mean you can’t appreciate these stunning temples of learning. Designed by some of the world’s greatest architects, these 10 libraries will expand your mind even if you never pick up a book.

1. Philological “Brain” Library at the Free University — Berlin, Germany

Designed by noted architect Norman Foster, a.k.a. Baron Foster of Thames Bank, this library on the campus of the Free University of Berlin, is in the shape of a human brain.

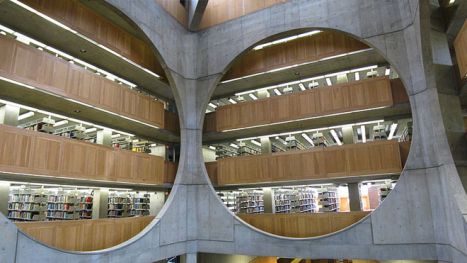

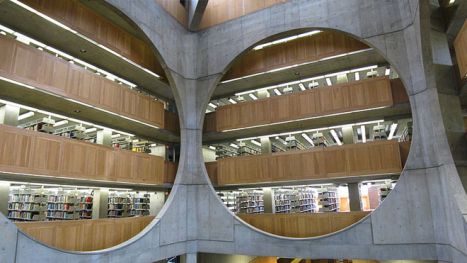

2. Phillips Exeter Academy Library – Exeter, New Hampshire

Phillips Exeter Academy Library was designed by renowned American architect Louis Kahn in 1965. Kahn structured the library in three concentric square rings, each one made from a different material, to give the visitor the sense that they are passing through buildings within buildings.

3. Cluain Mhuire Campus Library, Galway Mayo Institute of Technology — Galway, Ireland

Cluain Mhuire Campus Library was designed as a resource center for students and staff of GMIT who specialize in design, art, film and television. If this space doesn’t inspire them, it’s hard to imagine what will.

Continue reading for libraries 4-10

Monumental victims of dwindling finances, public backlash and political roadblocks, many designs from the world’s most celebrated architects never broke ground. Promising much in their form and magnitude, the stunning structures exist only as colorfully rendered visions on a lost landscape. Here, man’s best unmade plans.

Zaha Hadid's proposed Dubai Performing Arts Center was a 2009 victim of the global economic slowdown.

In his classic novel “Invisible Cities,” Italo Calvino envisioned a building, in a city called Fedora, containing a series of small globes. The visitor peering into each would see a small city, a model of a different Fedora. “These are the forms the city could have taken,” wrote Calvino, “if for one reason or another, it had not become what we see today.” In the real world, one can stand on a street in Manhattan and look into one’s iPhone, where the app “Museum of the Phantom City: Other Futures” reveals the New York that might have been: from the fantastic (Buckminster Fuller’s projected Midtown-covering dome) to the nearly realized (Diller and Scofidio’s Eyebeam Museum).

Architectural history is told by the victors, city skylines their monuments. But there are also missing monuments, those projects which, by dint of political folly, the capricious tides of public taste or simple financial overreach, never break ground. The credit crisis, for example, has turned a presumptive architectural fantasyland in Dubai, that emirate of excess—where submerged hotels or $3 billion cities in the form of chessboards were the order of the day—into a graveyard of gauzy renderings.

The financial collapse claimed so many schemes that the architectural and design provocateurs Constantin Boym and Laurene Leon Boym, known for their small metal replicas of such buildings as the Chernobyl plant (as part of the “Buildings of Disaster” series), began in 2009 to produce a series of so-called “Recession Souvenirs,” projects like Norman Foster’s Russia Tower. “But the series was short-lived,” says Constantin Boym, speaking from Doha, Qatar. “There was not much enthusiasm in this black humor any more.” (The few that were made, however, are highly collectible.)

As is suggested by their difficulty in getting built, unbuilt projects are often superlative in some sense, as much a statement as an edifice. Boris Iofan’s neoclassical Palace of the Soviets, for example, on which construction began in 1937, gradually morphed (with input from Stalin) into what would have been the world’s largest skyscraper. War intervened, however, and its steel frame was repurposed into bridges in 1941.

Norman Foster's Russia Tower. Photos: Renderings to Remember - These brilliant designs from some of the world's greatest architects never saw the light of day.

Even when absent, unbuilt projects can exert a curiously powerful hold on the cultural imagination: Étienne-Louis Boullée’s massively spherical 18th-century cenotaph for Isaac Newton still looms, like the Montgolfier balloon that was said to have inspired it, over the architectural landscape. The 1960s British proposal by Cedric Price for his Fun Palace, with its visual echoes in the Centre Pompidou, now looks prophetic.

Perhaps the most common, and salient, feature of unbuilt projects is that every architect, at some point in his career, will design one—or several. Will Jones, author of “Unbuilt Masterworks of the 21st Century,” says these are not necessarily negatives in an architect’s career. “If an architect can look back upon it without too much bitterness, it’s the perfect area to test out ideas,” he says. “It’s a proving ground, that they take on and can use in future buildings.” Jones notes that Richard Rogers’s Welsh Assembly building, for example, contains ideas from his unbuilt Rome Congress Center design, which itself, the firm notes, advanced themes from a competition for the Tokyo International Forum project.

The building itself hardly sailed to completion; Rogers was briefly fired from the project. But he ultimately avoided the fate of Zaha Hadid, whose Cardiff Bay Opera House, one of the most lamented unbuilt projects of the past few decades, crashed amid the rocky shoals of politics—nationalist, classist (The Sun denounced using Lottery funds for a project for “Welsh toffs”) and aesthetic. “It devastated us,” Hadid says. But this, and a subsequent slew of unbuilt competition entries, “tested our ideas on landscape topography, and you can see the results of this now in all of our work.” Hadid may be the only architect with two unbuilt opera houses (a project in Dubai was terminated), not to mention a celebrated—and built—opera house in Guangzhou, China.

Sometimes unbuilt projects turn out to have a rather unexpected second life. The young Danish architect Bjarke Ingels, whose firm designed the Danish Pavilion at the Shanghai World Expo, entered a competition in 2008 for a resort project in the north of Sweden. The firm lost the competition. But when they showed the work to a Chinese developer, he was struck by the fact that the building’s shape resembled the Chinese character for “people.” The firm hired a feng shui master, scaled the building up to “Chinese proportions,” and the “People’s Building” is now slated for Shanghai’s Bund.

With China’s expanding economic might, its low-cost labor, and relative lack of restrictions in blank-slate cities like Guangzhou, unbuilt projects have been a rarity. This is common in places where economic booms and cultural dreams conspire. As Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne argues, “Los Angeles was known for much of the 20th century as the city where anything—and everything—could and did get built, from massive subdivisions, to avant-garde houses clinging to hillsides, to hot dog stands shaped like hot dogs.”

On the flip side, however, sits another kind of “unbuilt” architecture—that which is torn down. And Los Angeles, Hawthorne says, rarely paused to reflect as it knocked down iconic architecture. Today, he says, with open land more scarce, seismic and other building codes constricted, it’s much harder to get things built. So now, as it is elsewhere, the destroyed and the unbuilt jostle in the collective imagination, and, as Hawthorne describes it, “the black-and-white photograph of the long-ago destroyed landmark is now joined in the collective imagination by the sleek digital rendering of the high-design project that couldn’t get financing.”

View Building’s slideshow

Article in WSJ

architects, architecture, modern architecture, modern buildings, new buildings, Urban Planning

|

Bjarke Ingels, Christopher Hawthorne, Constantin Boym, Invisible Cities, Laurene Leon Boym, Norman Foster, TOM VANDERBILT, Wall Street Journal, Will Jones, Zaha Hadid

|

Portugal’s Eduardo Souto de Moura, who has designed soccer stadiums, museums and office towers in his home country, is the winner of this year Pritzker Architecture Prize, the highest honor for architects.

Among his best-known buildings are the soccer stadium in Braga, Portugal, where European soccer teams fought for the championship in 2004; and the 20-story Burgo Tower office block in his native city of Porto, built in 2007. Souto de Moura, 58, has also built family homes, cinemas, shopping centers and hotels and since setting up his own office in 1980.

Jury Chairman Peter Palumbo said Souto de Moura “has produced a body of work that is of our time but also carries echoes of architectural traditions,” according to a statement today from the Hyatt Foundation, which awards the prize.

“He has the confidence to use stone that is a thousand years old or to take inspiration from a modern detail by Mies van der Rohe,” the statement said.

Souto de Moura worked for fellow Portuguese architect Alvaro Siza for five years before founding his own company. Siza won the Pritzker Prize in 1992.

Other previous winners of the prize, which is worth $100,000, include Norman Foster, Rem Koolhaas and Frank Gehry. The Hyatt Foundation established the prize in 1979 to honor a living architect.

YOU build it, will they come? That’s the basic question motivating plans to develop grand culture centres in otherwise derelict urban neighbourhoods. The idea is savvy: hire architects to build something beautiful (or at least something big), and then let the related businesses follow. This approach to urban rejuvenation—dubbed the “Bilbao effect” after Frank Gehry’s transformation of the Spanish city—has yielded some success stories, such as DC’s Penn Quarter (thank you Abe Pollin) and Minneapolis’s Mill District (the Guthrie Theatre is something else). Cleveland’s Gordon Square Arts District has essentially applied economic shock paddles to an entire area. But what about Dallas?

More than 30 years and $1 billion in the making, the Dallas Arts District is a 19-block area of museums and performance halls. It glitters with impressive buildings, including the handiwork of four Pritzker prize winners (I.M. Pei, Renzo Piano, Norman Foster and Rem Koolhaas). But Blair Kamin, the architecture critic for the Chicago Tribune, is not impressed. Alas, despite the “architectural firepower”, it is an “exceedingly dull place”:

There are no bookstores, few restaurants outside those in the museums and not a lot of street life, at least when there are no performances going on. Even some of the architects who’ve designed buildings here privately refer to the district as an architectural petting zoo—long on imported brand-name bling and short on homegrown-urban vitality.

Part of the problem is that Dallas lacks urban density, particularly in this area, so inevitably fewer people are milling about. Another hitch is that the buildings themselves are essentially competing beautiful fortresses—designed as grand monuments, not inviting public spaces. Some locals complain that they are clearly built for folks who drive in for a bit of culture and then drive away. Mr Kamin suggests that plans for a new park, which will bridge a sunken freeway and connect the district with a buzzier neighbourhood to the north, should create more pedestrian traffic when it opens in late 2012. Otherwise, he warns, Dallas may have just created “the dullest arts district money can buy.”

But surely it is possible to spend even more money to create an even duller arts district. Let’s take a moment to consider Saadiyat Island, the sprawling arts development taking shape in Abu Dhabi. Like the arts district in Dallas, Abu Dhabi has imported a series of bling-bling names for some serious starchitecture. Frank Gehry has designed the new $800m outpost of the Guggenheim (pictured top; 12-times the size of the New York flagship and in need of a new art collection by 2015); Jean Nouvel, the Pritzker-winner who designed the Guthrie Theatre, is creating the Abu Dhabi branch of the Louvre; Norman Foster is designing a museum of national history; and the matter of density may be solved by new luxury resorts and villas. As for bookstores and cafe culture, surely the mesmerising mess of the Gehry building will make it impossible to read and unnecessary to caffeinate.

The Guggenheim Abu Dhabi has been in the news a lot lately, owing to a possible boycott of more than 130 artists over the working conditions of those charged with erecting these modern temples. But setting aside this public-relations disaster, which could significantly hamper the Guggenheim’s work in filling this museum, the Saadiyat complex poses a larger question: will people come? Is it enough to build these gigantic monuments to modernity (in an otherwise not-so-modern and remote place) and assume that the razzle-dazzle will lure the tourists? Dallas’s experiment illustrates the flaws in developments that consider the needs of architecture at the expense of people. A culture district without the glue of wandering pedestrians (or an atmosphere of working artists; or let’s face it, streets) may struggle to earn its keep.

Via The Economist

architecture, architecture critic

|

Abu Dhabi, Bilbao effect, Blair Kamin, Chicago Tribune, Guggenheim, I. M. Pei, Louvre, Norman Foster, Pritzker prize winners, Rem Koolhaas, Renzo Piano, Saadiyat Island

|

BY Cliff Kuang

Tue Jun 9, 2009 at 11:00 AM

Which architects have the most unusual, influential visions for the field?

1. Will Alsop, ALSOP Architects

Few architects have been so dedicated to such an unusual design aesthetic as maximalist Will Alsop. And fewer still have been as successful at building their designs. His nearly completed

“Chips” building was inspired by piled french fries; his extension for the Ontario College of Art and Design is one of the strangest, most exciting buildings in recent memory:

ALSOP Architects

aia, architects, architecture, architecture critic, buildings, modern architecture, modern buildings, new buildings, skyscraper

|

2010 Shanghai Expo, ALSOP Architecture, Beijing, Beijing International Airport, Bird's Nest Olympic Stadium, Book Mountain Project, Cairo, CCTV Tower, Centre Pompidou Metz, Chips Building, Cliff Kuang, Erdos Museum, Expo City, Foster + Partners, Herzog & De Meuron, High-rise pig farm, Insuk Cho, Jacob van Rijs, Jacques Herzog and Pierre De Mueron, Kisu Park, Korean Pavilion, MAD Architects, MASS Studies, Morphosis Architects, MVRDV, Nathalie de Vries, Norman Foster, OMA, Phare Tower, Rem Koolhas, Shigeru Ban, Shigeru Ban Architects, Terminal 3, Thom Mayne, Will Alsop, Winy Maas, Yansong Ma, Zaha Hadid, Zaha Hadid Architects

|