By Nate Berg

From entry-level interns to top-tier management, the business of architecture relies on smart workers [staff]. To stay competitive and endure an ever-turbulent job market, design firms need to recruit the best and the brightest while holding on to the skilled talent they already have.

Look for Inquisitive Minds

When seeking new talent, New York–based Robert A.M. Stern Architects partner Graham Wyatt, AIA, says firms should look broadly at the candidates’ talents. Architectural ability and design skills are obviously important, but they shouldn’t be the only factors considered. “Look for people who are broadly educated and, beyond that, people who are inquisitive about the world, who are not just one-dimensional,” he says.

Incentive High Performance

Rewarding employees based on the quality of their work will push them to excel and make them feel appreciated. Robert A.M. Stern Architects uses a system as part of a profit-sharing model that, when the firm is in the black, issues an additional bonus to employees based on annual reviews. “The principle of it is important to the culture of our firm, which is to reward people at all levels so they feel that they’re pulling in the same direction,” Wyatt says, “and that’s really essential to our success.”

Respond to Shifts in Supply and Demand

The layoffs during the recession may seem like fresh wounds, but the market has recovered. Demand for architects is high now due to increased work and a limited supply of professionals. “Twenty to 30 percent of the architectural workforce left in the last recession, so the talent pool is much smaller,” says David McFadden, CEO of Consulting for Architects, a staffing agency. Firms need to recognize that it’s a seller’s market. “Architects are just not sitting on a department store shelf anymore.”

Evaluate Routinely

Regular performance reviews are crucial for employers to track progress and for workers to get positive feedback, constructive criticism, and, ideally, a chance to request a raise. Communication is mutually beneficial, but it sometimes doesn’t happen enough. “In some firms, the annual review only happens every two or three years,” says Herbert Cannon, president of consultancy AEC Management Solutions. “That can be demoralizing to employees.”

Be Less Picky, Hire More Quickly

A dearth of architects means employers need to adjust expectations and perhaps lower their hiring standards. The perfect candidate simply might not exist. “There’s still this perception that there’s people available that meet all of your criteria. But in fact there’s not and so you need to make a quick attitude adjustment,” says McFadden. To top it off, the limited supply is in such demand—the candidates you want may be under consideration by other firms. McFadden suggests acting quickly: “Shorten the time from receiving a résumé to scheduling an interview to making an offer. … You have to be quick; otherwise you’re going to lose out to a firm that is.”

Honor Loyalty

Firms need to know how to hold on to what they’ve got. That was easier during the recession when many architects were happy to have any job. But now that things have turned around and opportunities are opening up, employers need to do more to keep their workers from perusing the job boards. McFadden says firms should increase compensation for the people who stuck with them during the recession, and even more so for those who saw years pass by without a raise.

by Nate Berg for Architectmagazine.com*

*This article was not written for The CFA Blog. This article was written for Architect Magazine.com and reposted by CFA for the CFA Blog.

Editors note: Obviously, we contributed to this article, and agree with the points Nate makes. Do you agree that the hiring trend favors the applicants?

Search Careers

Request Talent

Join Mailing List

Architecture Hiring

|

AIA NY, American Institute of Architects, Architect, architects, architecture, Architecture billings index, business, Consulting For Architects, David McFadden, Hiring Demand, jobs, RAMSA, recession, Rewarding Employees, Robert A.M. Stern Architects, Salary Increase, Staff, Staff Retention, unemployed architects

|

Employers Ask. They All Got Jobs.

6 Crucial Ways to Repopulate Your Workforce

Introduction

Unemployment rates are still uncomfortably high across the nation, there is a misperception that architectural talent must be plentiful, but for specific experience, the exact opposite is true. The shortage is so acute that it has been associated with a rise in offshoring, a bidding war and comparisons to college recruiting. To secure the architecture talent they need, hiring managers must adopt a competitive hiring strategy or lose to someone who does.

Architects had to get even more creative after the economic recession that began around December 2007. The built-in versatility from their studies in areas such as civil engineering, math, art history, and physics positioned them well for thinking outside the box. Jumping ahead seven years, the demand for architectural talent in the wake of the recession has re-stabilized, but talent availability lags behind. No hiring firm could have possibly predicted this rapid shift. To remedy the imbalance between supply and demand, hiring firms must shift their perception of what is viable and consider potential candidates on more realistic criteria.

Supply and Demand

Within the last 10 years, supply and demand in the architecture industry have moved in opposite directions. Uncertainty about capital access discouraged building development, leading to dormant projects and a lack of ambition in both the commercial and residential markets. In 2012, a study by Georgetown University revealed that architecture graduates had experienced the highest rate of unemployment (13.9%) when compared to other fields. Prior to the recession, this problem was not nearly so pronounced.

The Recession’s Effect

The poor economy challenged architects to get creative. According to the Department of Labor, 39,900 jobs were lost in 2010 alone. Architects were forced to think flexibly in order to sustain a livelihood and many did. For example, take 26-year-old architect Natasha Case: she was laid off from a prestigious position at Walt Disney Imagineering. Within a year, Case developed a homemade mobile ice cream business with a friend. Flavors were inspired by architecture. One such flavor was the “Frank Behry,” named after renowned architect Frank Gehry. The startup was such a hit that Case’s former employer, Walt Disney Imagineering, became a customer.

Case is not the only person who resorted to new endeavors during the recession. After years of uncertainty, architects have settled into new careers both in and outside of the industry, leaving the talent pool depleted.

Demand is Rapidly Growing

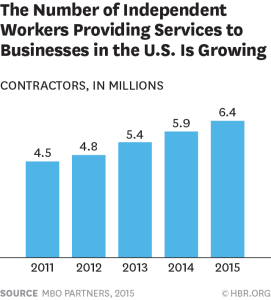

As the architecture industry attempts to bounce back from economic instability, the landscape has changed significantly. According to MNI News, hiring firms in New York, Los Angeles, and North Carolina report explosive growth; the American Institute of Architects released a billing index in August 2014, showing its highest growth rate since 2007. There are no signs of this pattern slowing.

Industry spending is projected to increase by 10 percent for non-residential construction in 2015. Kermit Baker, chief economist at the American Association of Architects, attributes this growth to more capital access and recovering business confidence.

Institutional projects, which were sluggish in early 2014, are generating growth as well, with public, private and charter school projects popping up in New York City, Long Island, and beyond. Better access to capital has allowed for the renewal of projects that were once dormant, and for the launching of new ones. The Housing Studio, an 18-year-old firm in Charlotte, North Carolina, is billing at its highest rates.

According to the Federal Reserve’s economic forecast, growth is expected to rise 3 percent in the second half of 2014, followed by another 3 percent in 2015. At the same time, the national unemployment rate is projected to fall to 5.5 percent in 2015. Design projects are regenerating, demand snowballing nationally, and architectural demand outpaces supply.

The Talent Pool

Like Natasha Case, many architects have scattered into new industries since the recession. Architecture graduates have been forced out of the field due to a lack of opportunities and inadequate levels of experience.As many hiring firms know, several factors must fall into place for talent to be hired for a project. Candidates are expected, at a minimum, to be proficient in design software, have at least three to seven years of experience in a specific type of work, be eligible to work in the U.S, and be a good cultural fit. The rise in both residential and commercial design projects in 2014 qualified architects, who are still in the talent pool, simply cannot meet the demand.

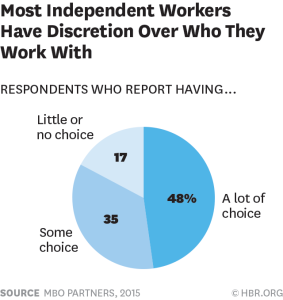

On top of this, federal and state laws provide a slew of other obstacles for hiring firms to secure the right candidates. Even small firms must comply with the requirements laid out by the Affordable Care Act and the Department of Labor and Homeland Security. Further complications arise when determining exempt vs. nonexempt employees, contractors and overtime eligibility. Considering this myriad of complications, it is no surprise that firms are experiencing an imbalance of supply and demand.Aside from this, cultural changes have caused Millennials to leave their firms after an average of just three years. This puts an extra layer of pressure on firms to continuously cycle through the recruitment process. Retention levels have dipped due to this shift toward a freelance-style career.

In combination, these factors lead to significant stress and a continuous lack of stability at firms, who must constantly process recruitment materials and decide on new candidates. A simple attitude adjustment by hiring firms is necessary for the industry to regain its economic footing. This does not refer to a lowering of standards but rather an expansion in considerations during the hiring process.

In Order to Compete for Quality Talent, Hiring Firms Must Be More Flexible in 6 Crucial Areas:

1. Experiential Requirements

Considering the sluggish pace at which design projects progressed in recent years, newer architects were unable to acquire extensive experience in various areas. With larger commercial projects handed off to established architects, those with less experience are continuously overlooked.

2. Cultural Fit

While a person’s character and their ability to mesh with current company values are important, the decision to hire should primarily be determined by the candidate’s ability to execute the design. Assessing perfect cultural fit is generally a matter of opinion, best made flexible during times of talent shortages.

3. Compensation

Considering the level of competition currently face by hiring firms who are in need of talent, flexibility in compensation is crucial. Approaching candidates confidently with a reasonable figure will motivate them and assure them that they are in the right place.

4. Hiring Time

Architects are at an advantage as the industry currently stands. When the correct candidate is found, hiring firms should work to reduce the time between the initial meeting, and the extension of an offer; under lengthier circumstances, architects may move on to other available firms.

5. Employment Duration

While it may be frustrating for both firms and architects to be floating in a sea of uncertainty, this post-recession period of adjustment are unavoidable. It’s worth considering a candidate regardless of the amount of time he or she plans to stay with a firm, and the training time required.

6. Project Placement

In a talent shortage such as this, it may not be feasible to have every employee working as a full-time staff member. While it may sound like a hassle, temporary employees can provide the extra energy burst needed to push a project beyond original expectations. These employees could also serve as a more objective third party with unique backgrounds and perspectives while stabilizing the peaks and valleys associated with architectural practice.

Conclusion

As projects slowly resume and capital becomes available, a full recovery from the recession is in sight. The final puzzle piece involves architects being reacquainted with hiring firms. At least a few decades will pass before for the talent pool can catch up with demand. With many senior architects out of the game for good, and waves of graduates who’ve yet to mature, this problem won’t diminish anytime soon.In order to bridge the gap, hiring firms must be willing to adapt. If the above changes are implemented, hiring firms will be better able to thrive in the industry’s current climate.

Search Careers

Request Talent

Join Mailing List

Author: Lindsay Van Thoen December 20, 2013; for the Freelancers Union

What happens when you tell someone you’re a freelancer?

In my experience, you’ll probably get some version of the following:

1. “I wish I could work in pajamas and sleep in every day!”

There may be some freelancers who don’t have to leave their house, spend their days watching Mad Men reruns, and only work 4 hours a day — but honestly, I haven’t met one yet.

Most freelancers are too busy going to client meetings, meeting with prospective clients, working out of the client’s office, going to networking events, working around their families’ schedules, and, you know, running their own business.

The idea that freelancers are sloppy and carefree somehow implies that freelancers just don’t work as hard as 9-5-ers. Not true!

2. “Ugh, the economy is so tough.” (I.e., freelancing is not a real job or people are only freelancers because they can’t find a real job.)

While it’s true that many traditional workers didn’t start freelancing by choice, it doesn’t mean that freelancers are poor, miserable souls who can’t wait to crawl back to corporateville.

Many freelancers either go independent by choice or find they like freelancing better, whether it’s because of more autonomy or better work/life balance or a host of other reasons that don’t involve desperation and agony.

It’s true that freelancing still doesn’t have the status of a C-level position in most fields. I expect that as more workers go freelance, a more realistic perception will develop: there are bad freelancers and good freelancers, happy freelancers and miserable freelancers, experienced and inexperienced.

We’ll soon see workers as whole people with a set of skills and services, not as the position they’re in.

3. “It must be so nice to never have anyone order you around!”

Wouldn’t it be great if this were true?

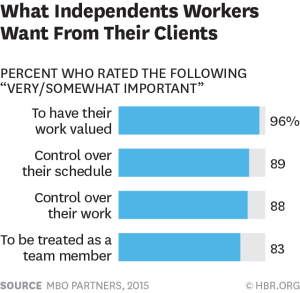

It’s true that freelancers are their own bosses — but sometimes, to maintain a good client-freelancer relationship, you have to let the client have what they want.

The best clients do say: “Here is the task I want, here are my expectations, I trust you to complete it well.” There are also clients who micromanage you the whole way. And a whole host of other people who think “freelancing” means “lowest rung on the totem pole that I can treat any way I want.” This is where freelancers have to educate clients about proper relationships and expectations.

4. “You must always have such exciting work!”

One of the best things about freelancing is that, to a certain extent, you get to choose the projects you’ll work on. If you work in a creative field, you’ll also be able to develop your own unique style/niche/speciality, so that people who come to you want YOU, and let you be your whole self.

But there are going to be boring days. There are going to boring projects or boring revisions or boring accounting.

Also, some freelancers are happier doing work they’re good at for steady clients than having constant new/exciting projects. They love the time they have with their family and they love the flexibility more than they love every single project they work on.

5. “Freelancers pad their invoices — you can always get them to negotiate down their fees.”

You probably won’t hear anybody say this to your face, but they will say it behind your back!

First, many freelancers are actually undercharging for their services. That’s because many people who go into freelancing assume that they should charge the hourly rate they got when they were an employee.

No. You need to charge that hourly rate, plus what you used to get for benefits that you now have to pay for yourself (~20-30%), plus an estimate of how much time it takes to land the client and ancillary things (like invoice filling), plus any equipment costs (like computers). This is an accurate representation of your value, not padding.

Freelancers who undercut the market rate hurt all freelancers and set expectations for cheap work.

6. “I could never freelance — I have too many financial obligations. It’s so insecure!”

The truth is that every job is insecure. Markets change, companies close or downsize.

The only security you have is the ability to provide a service of value that someone is willing to pay for. Your security is you. This isn’t a mindset, it’s a set of actions — all of which are easier said than done.

Smart freelancers make themselves recession-proof by having multiple income streams, constantly marketing themselves and forming new connections, and staying flexible by learning new skills, new programs, new fields.

When the economy leaves a smart freelancer in the lurch, he/she can pivot skills or rely on another income stream. Traditional employment can give one the illusion of stability, and that in itself is pretty risky!

What other myths about freelancing have you heard?

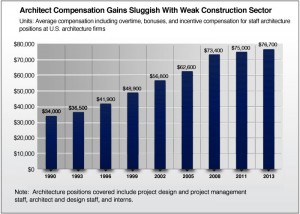

Lingering impact from the Great Recession slows gains in salaries

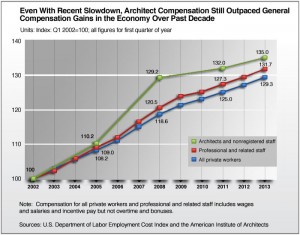

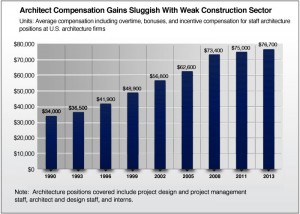

Over the last several years, most architecture firms have benefited from a general improvement in the economy as well as in the construction sector. Revenue at architecture firms increased almost 11 percent in 2012 from 2011 levels, according to U.S. Census Bureau figures, and firm payrolls have followed suit. But this modest improvement in business conditions has done little to lift compensation levels at firms. Between 2011 and 2013, average total compensation for architecture positions—including base salary, overtime, bonuses, and incentive compensation—increased only slightly over 1 percent per year, barely more than the average increase in compensation between 2008 and 2011, when the construction sector was still in steep decline.

Even this modest 1 percent increase in average architect compensation may overstate the experience of the typical architect during this period. Average compensation depends on the mix, by experience levels, of positions reporting. Since many less experienced architecture positions were eliminated during the downturn, current average compensation may reflect a higher share of more experienced (and more highly compensated) positions. Regardless, while average compensation for architecture positions increased a mere 0.7 percent per year compounded between 2008 and 2011, growth increased to only 1.1 percent per year between 2011 and 2013 (Exhibit 1.1).

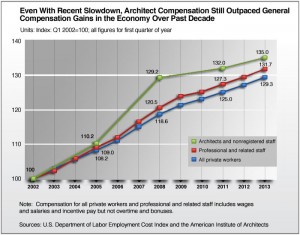

Architecture staff compensation tends to be more volatile over the business cycle than compensation for most other occupations. Over the past decade, compensation gains for architecture positions have more than kept pace with compensation across the entire economy. Architecture compensation increased 35 percent between early 2002 and early 2013, compared to just under 32 percent for all professional and related staff (typically defined as white-collar workers such as lawyers, accountants, etc.), and just over 29 percent for all private-sector workers (Exhibit 1.2).

Compensation levels vary by firm size

Historically, large architecture firms have offered higher levels of compensation. These comparisons are more difficult for more senior positions because job responsibilities are difficult to compare across firms of different sizes. However, this disparity exists even for positions with relatively standard job descriptions such as Intern 1 or Architect 1.

At firms with fewer than 10 employees, Intern 1 compensation averaged 10 to 15 percent below national averages. At firms with more than 250 employees, Intern 1 compensation averaged more than 10 percent above the national average. A similar pattern held for Architect 1 positions: about 10 percent below the national average at firms with fewer than 10 employees, and almost 10 percent above the national average at firms with 250 or more employees.

Staff turnover and fringe benefits reflect improvement

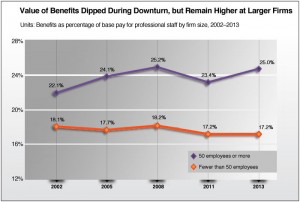

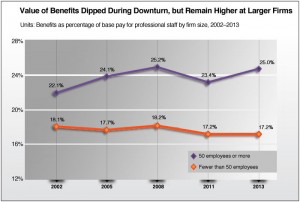

Another sign that business conditions have stabilized across the profession is that benefits offered to employees have begun to modestly improve at many firms. While declining between 2008 and 2011 as firm revenues eroded, they rebounded modestly by 2013, with benefits packages averaging 18 percent of base salaries for professional staff. Benefits have bounced back faster at larger firms and remain significantly higher than those offered by smaller firms (Exhibit 1.3).

Recent Related:

AIA Compensation Survey: Architect Compensation Stagnant

Reference:

Purchase the 2013 AIA Compensation Report

New for 2013: Architect Compensation by Metro Area

Back to AIArchitect August 9, 2013

Go to the current issue of AIArchitect

Architecture Practice

|

aia, AIA NY, American Institute of Architects, architecture, Architecture billings index, Base Salaries, business, Compensation, economy, Great Recession, jobs, recession, Revenue, U.S. Census Bureau, unemployed architects

|

Could these words be costing you your dream job?

By Catherine Conlan, Monster Contributing Writer

Hiring managers and HR pros will often close out a job interview by asking an applicant if he or she has any questions themselves. This is a great opportunity to find out more about the job and the company’s expectations, but you can’t forget that the interviewer hasn’t stopped judging YOU. Here are 5 questions that can make a bad impression on your interviewer, scuttling your chances for getting the job.

1. “When will I be promoted?:

This is one of the most common questions that applicants come up with, and it should be avoided, says Rebecca Woods, Vice President of Human Resources at Doherty Employer Services in Minneapolis. “It’s inappropriate because it puts the cart before the horse.” Instead of asking when the promotion will occur, Woods says a better approach is to ask what you would need to do to get a promotion.

2. “What’s the salary for this position?”

Asking about salary and benefits in the first interview “always turns me off,” says Norma Beasant, founder of Talento Human Resources Consulting and an HR consultant at the University of Minnesota. “I’m always disappointed when they ask this, especially in the first interview.” Beasant says the first interview is more about selling yourself to the interviewer, and that questions about salary and benefits should really wait until a later interview.

3. “When can I expect a raise?”

Talking about compensation can be difficult, but asking about raises is not the way to go about it, Woods says. So many companies have frozen salaries and raises that it makes more sense to ask about the process to follow or what can be done to work up to higher compensation level. Talking about “expecting” a raise, Woods says, “shows a person is out of touch with reality.”

4. “What sort of flextime options do you have?”

This kind of question can make it sound like you’re interested in getting out of the office as much as possible. “When I hear this question, I’m wondering, are you interested in the job?” Beasant says. Many companies have many options for scheduling, but asking about it in the first interview is “not appropriate,” Beasant says.

5. Any question that shows you haven’t been listening.

Woods said she interviewed an applicant for a position that was 60 miles from the person’s home. Woods told the applicant that the company was flexible about many things, but it did not offer telecommuting. “At the end of the interview, she asked if she would be able to work from home,” Woods says. “Was she even listening? So some ‘bad questions’ can be more situational to the interview itself.”

With the economy the way it is, employers are much more choosy and picky, Beasant says. Knowing the questions to avoid in an interview can help you stand out — in a good way.

It’s hard to miss the chatter these days about creative thinking and it’s importance going forward in the new ideas based, connected economy.

Richard Florida says creativity drives theeconomy (http://zite.to/11HzQyZ). Peter Arvai calls it the “Frictionless Economy (http://zite.to/11Wsa2b) where he states;

“Companies that are succeeding rely on creative thinking to consistently produce new ideas”

More Arvai;

“Creativity is becoming the single most defining characteristic of an organization’s ability to survive. We’ve moved into an idea economy where success can be very profitable and short at the same time. To be a contender, companies have to be built around idea production and guided by an actual purpose for existing.”

Hey, I get it. The business world is constantly in flux and adaptability and innovation are the keys to success. So who is better suited to guide business through innovation and idea production than the original creative thinkers?

You guessed it, architects and designers. We ARE the original creative (design) thinkers. It’s what we’ve been trained to do. Trained to dissect problems, assimilate information, connect dots and see patterns before anyone else sees them. Trained to innovate as we strive to create a better built environment. Trained to ask why and find a better way. We think, creatively all the time. So my question is:

What took the business world so long to catch up?

Architects and designers have always know there is only one way to think.

Creatively.

Our way.

So if you see a forlorn businessperson muttering to themselves about how to compete in today’s business world throw an arm over their shoulder, smile and say it’s going to be okay.

The thinkers are here.

Robert Vecchione is an original thinker. Architect/designer, principal at Cobrooke Creative, a multidisciplinary firm generating ideas for business to help them sharpen and define their purpose. www.cobrooke.com